Topic

Petr Dub looks back on 25 years with Physics from HRW

At the end of 2025, the third edition of the well-established, modernly conceived textbook Physics by D. Halliday, R. Resnick, and J. Walker—informally known as HRW—was published by VUTIUM Publishing House. Editor of the textbook Petr Dub from the Institute of Physical Engineering at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering BUT, who is quite literally its spiritual father, told us about his 25 years with HRW.

What was the situation regarding teaching materials for physics education here before the first edition of the American publication?

Physics is taught at the beginning of studies at all technical universities, and a high-quality textbook is therefore absolutely essential. Nevertheless, for a long time we lacked a modern university-level textbook that would meet contemporary requirements in terms of content, didactics, and graphic design. Already in the 1970s and 1980s there were efforts by physicists to publish a translation of a proven Western textbook, but for political reasons this was not possible, and students had to make do with lecture notes. The situation in Slovakia was more favorable at the time. In the 1980s, a translation of the famous Feynman Lectures on Physics was published there; however, these were too demanding for beginning students of engineering disciplines.

What opportunities did the post-revolutionary period bring?

We began considering the publication of a translated physics textbook immediately after 1990. The question arose: why translate, and not create an original textbook? The answer was simple—why recreate something that had already been thought through, tested, and verified over decades in many countries around the world? The decision to publish a translated textbook was made in 1999, when issuing a modern physics textbook that would improve teaching not only at BUT but also at other universities presented itself as a meaningful contribution to commemorating the importance of our university in the year of its 100th anniversary. At that time, I served as Vice-Rector for Educational Affairs and was also responsible for the newly established VUTIUM Publishing House. Together with the then director of the publishing house, Alena Mizerová, who had extensive publishing experience, we believed we could manage the project.

Choosing the right title for translation was probably not easy.

Was it difficult to obtain approval for the Czech edition?

Negotiations with John Wiley & Sons, one of the world’s largest publishers of scholarly literature, took some time. They tested us. VUTIUM Publishing House was young at the time and practically unknown internationally. After about a year of negotiations, however, we signed the contract for the Czech edition and could begin the work.

Who all worked on the translation of the book?

The textbook had nearly 1,200 pages, and our goal was to publish it as soon as possible. Therefore, 25 colleagues from BUT as well as from the Faculty of Science at MU and the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University participated in the translation. Such a large team also brought challenges—it was necessary to thoroughly unify the text and edit it linguistically and professionally. I undertook the final editorial work together with Jan Obdržálek from the Prague Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, placing emphasis on readability and language quality. Colleagues from the Institute of Physical Engineering at FME played a significant role in preparing the translation, as great importance has always been placed there on high-quality physics education. A major contribution in this respect was made since the 1970s by Prof. Ivan Šantavý, who was among the physicists already striving at that time to have this book translated.

We also searched for a suitable Czech title. Ultimately, the title Fyzika with the subtitle Fyzika sympaticky (“Physics—Approachably”) was created. Because a good textbook should be a reliable and friendly guide for students and at the same time a good and inspiring aid for teachers—and in this sense, sympathetic.

Did you take into account differences between the American and Czech environments in the translation?

A textbook translation must reflect the teaching methods of the specific environment, so many things needed to be adjusted and changed. We were in contact with Professor Walker during this process, consulting the adjustments and changes with him, and he deserves thanks for his interest. The work on preparing the book was more complex and longer than we had anticipated. The book was published in 2001 in a print run of 5,000 copies—500 in hardcover and 4,500 as a set of five paperback volumes. It was sold not only in the Czech Republic but also in Slovakia, and the print run quickly sold out. Updated and revised reprints followed in 2003 and 2006, each with a print run of 2,000 copies.

The project was financially demanding; however, thanks to a contribution from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and financial support from BUT partners for printing, it was possible to set a favorable price for students.

What did the publication of Physics mean for VUTIUM Publishing House?

By translating Physics, VUTIUM entered international awareness. Immediately after publication, we also presented it at the well-known international Frankfurt Book Fair, and I recall a very pleasant meeting with representatives of John Wiley at our stand—this opened the door to cooperation with other foreign publishers. Negotiations with them were already swift.

The success of Physics showed that it was not only appropriate but also possible to prepare translations of other textbooks. Physics thus became the first volume in the series Translations of University Textbooks. In 2010, a translation of the textbook Engineering Design was published, whose second edition appeared recently. This was followed by the textbook Organic Chemistry, whose Czech edition was prepared by colleagues from our Faculty of Chemistry and the Prague University of Chemistry and Technology.

The great interest in Physics soon required another edition…

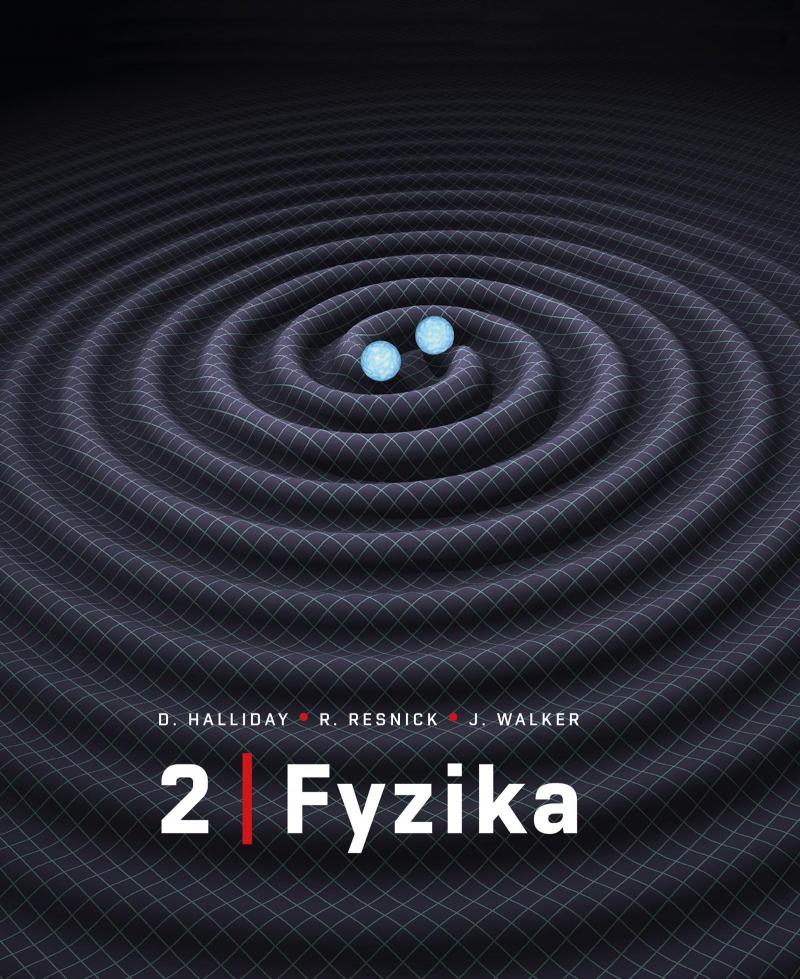

The textbook was positively received not only by students and teachers at universities and secondary schools, but also by the general public, and sustained interest led to the preparation of the second Czech edition of Physics (based on the eighth, substantially revised American edition), which was published in 2013 with a print run of 3,000 copies. Reprints of the second Czech edition followed in 2019 and 2021, each with a print run of 1,500 copies. Immediately afterward, work began on the third, revised Czech edition based on the tenth American edition.

How does the newly published edition differ from the previous ones?

The new edition, again published in two hardcover volumes, primarily introduces a modern modular organization of chapters. Each module begins by defining learning objectives titled What We Will Learn and Understand and an overview of key insights that help students focus on essential ideas. An important component of the textbook is the reflections that motivate study of the respective section. Each chapter opens with the question What Is It About and How Do We Approach It?, and a brief answer explains why the topic is studied and how to approach it.

Attention was also paid to revising the illustrations. Images containing a large amount of information were divided into several parts to make their message clearer and more comprehensible, and text boxes facilitating orientation were inserted into most of them. The connection between text and image makes the study of physics more illustrative, accessible, and engaging, and the images thus also contribute to creating a better memory trace.

Can a textbook shed light where live explanation has difficulty reaching?

The path to understanding the simple within the complex is longer than previously assumed. A good textbook has exceptional potential in this regard. Explanation alone is not enough—understanding arises through repeated qualitative reasoning about various problems. Precision must go hand in hand with clarity and concreteness, because the path to abstract thinking is long and complex, and students reach it gradually, step by step. Physical concepts often contradict intuitive notions and must be systematically and convincingly corrected through discussion of appropriate problems and exercises.

What does HRW mean to you personally?

I am glad that Physics, known as HRW, has influenced teaching not only at universities but also at secondary schools and has become a reliable guide to the world of physics for many students and teachers. I worked on the latest edition in 2022, then in 2023 and 2024, up until the summer of 2025, and I enjoyed it immensely. I took the materials with me on vacation and worked on them in various places dear to me—sometimes in the castle gardens in Rájec or Lysice, sometimes in Šumava or Luhačovice. As a result, I associate the book with specific places and experiences and know exactly which chapter I worked on where. One could say that I have the book in my head.

Solid-state physics, which you studied at MU, has accompanied you throughout your professional life. What was your original impulse to study physics?

My interest in physics and mathematics arose already in elementary school, which is why I went to Křenová Grammar School, where there was a class focused on mathematics and physics. The so-called normalization period was bleak, but the school environment was pleasant. We were also taken care of by Professor Košťál, who worked at BUT and led physics seminars for interested students at our grammar school. He was also the founder of the Physics Olympiad, which is now in its 63rd year. I participated in that Olympiad from ninth grade, so I was well trained, and my choice to study at the Faculty of Science at MU was entirely natural. After graduating, I stayed for a year on a study stay, and although I was not a party member, after certain vicissitudes I remained for another three and a half years in an internal postgraduate program.

Nevertheless, in 1984 you joined BUT, which you have never left. Was there a freer spirit there?

At that time, there was not such strict party supervision at BUT, and I joined the then Department of Physics (from which the current Institute of Physical Engineering emerged in the early 1990s), where a pleasant and creative spirit prevailed. Perhaps they took me also because I was willing to accept a half-time position, which later became full-time. At the same time, however, I was involved at the Faculty of Science in cooperation with Tesla Rožnov. That cooperation continues to this day through the American multinational company onsemi, which supported the second and third editions of Physics.

Can one say to what extent physics as a science develops or ages, or is it rather timeless?

Physics naturally develops, yet in a certain sense it has a timeless character. What is essential about physics—and about the natural sciences in general—is that new theories usually do not abolish previous ones but rather delineate the domain of their validity. The development of physics thus gradually reveals the limits within which individual theories can be used. Until the end of the 19th century, there was so-called classical physics. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, quantum theory and the theory of relativity emerged, showing the limits of its validity. Very briefly put: today we know that classical physics excellently describes phenomena at low velocities compared to the speed of light and for macroscopic objects. The exposition in the textbook therefore naturally begins with classical mechanics and Newton’s laws, while at the same time emphasizing the conditions under which they can be applied. These issues are then addressed in later chapters dealing with the theory of relativity and with quantum and atomic physics.

How would you motivate applicants to study physics?

Motivation may depend on the mindset of individual applicants. Some may be intrigued, for example, by the question: Do you want to see an atom? That in itself is exciting. And we can answer: Yes—even though an atom is invisible, we can “see” it, for example using a scanning tunneling microscope, which is discussed in the book. For more pragmatically oriented applicants, another argument is important: people who go through education with a strong physics component gain a certain advantage. They learn to think systematically not only about physical problems but also about other issues and become extraordinarily flexible. As a result, they find very good employment. After all, many top managers of the largest banks in France are physics graduates—precisely because they have learned to think analytically. If I stay within our field of Physical Engineering and Nanotechnology, we have a whole range of graduates who find employment not only in our high-tech companies such as Tescan, Thermo Fisher Scientific, onsemi, or Meopta—which, incidentally, are the companies that supported the latest edition of the book—but also abroad, for example as doctoral students at high-quality universities. If someone has the interest and aptitude for physics, they certainly will not make a mistake by choosing to study it.

The book is already on sale, but it has not yet been christened.

We will christen it in mid-February, once students have settled into the summer semester. The first edition of the textbook was christened in Aula Q at FME, and the program was opened by a lecture by the well-known astronomer Jiří Grygar. This time, I plan to invite Professor Podolský, who is an expert on gravitational waves, and the cover of the new edition features a motif of the merger of two black holes emitting gravitational waves. We already know that there is great interest in the book, so it can be assumed that, as always, another reprint will follow after three years.