People

Petr Viewegh’s Microcosm and Macrocosm

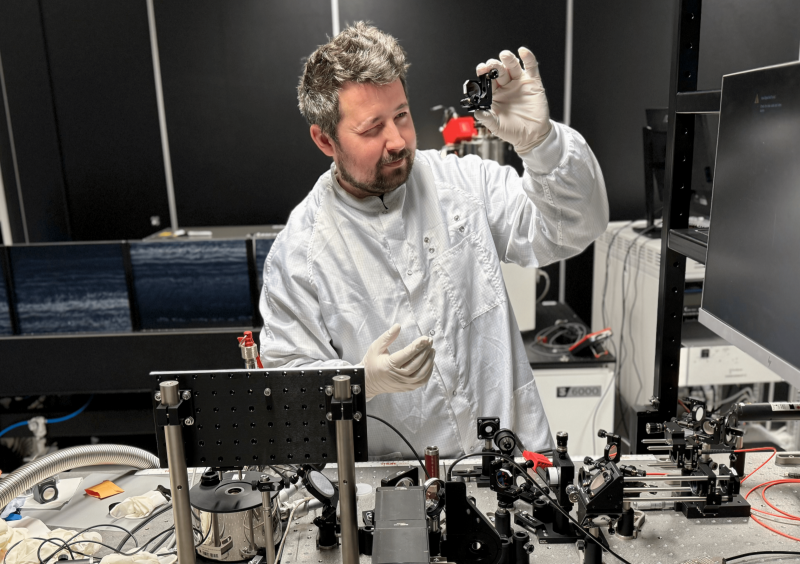

His name is known way beyond a small circle of scientific insiders. Petr Viewegh (formerly Dvořák) popularises natural sciences among the general public through his lectures, astronomy camps, and other activities. He is successful at that because he is able to talk about complex fields such as astrophysics, quantum mechanics, or nanophotonics in a way that is clear and attractive for the layman. While in nanotechnology laboratories, he solves sophisticated scientific problems with the help of state-of-the-art instruments, in private, he remains a “simple village boy” whose path to physics was by no means straightforward. Our conversation, therefore, did not only revolve around his work in nanophotonics and the projects he is involved in at CEITEC BUT, but we also got a glimpse into Petr’s extraordinary personal story and touched upon universal themes related to physics and scientific research.

Petr, you are known, among other things, as an astronomy and natural sciences communicator, even among the youngest generations, for whom you organize, for example, astronomy camps. So the first question is: when did you develop a passion for space and physics, was it when you were a boy?

Thank you for this question. My story is a bit long and convoluted, so if you allow me, I’ll talk a little bit. As a diagnosed dysgraphic and dyslexic who had huge problems with dictation, for example, I was definitely not destined for a career in education. I loved cooking and was determined to train as a chef. At the same time, I was good at physics and mathematics, so I was sent to a physics competition, where I succeeded and was rewarded with an astronomy book by the Czech author Jiří Rada. It was thin, so I managed (laughs). What fascinated me about the book was how it connected the universe with mathematics, showing what you can calculate. So I wished for more literature on the subject and found my great hobby in astronomy. But I still wanted to become a chef.

And what happened next?

In the ninth grade, my mother persuaded me to apply to a technical school in addition to the chef’s apprenticeship. So I tried the Secondary School of Industry at Jihlava, where the entrance exams only tested physics and mathematics. Well, I got in without any problems. In Jihlava, I started attending the astronomy club, and through a physics correspondence competition, I got acquainted with my peers from secondary schools, the best physicists of their years. They started to teach me physics and mathematics, and I was able to offer them a more practical approach to life and science. In that physics correspondence competition, there was always an experimental problem alongside the classical theoretical examples, and that was my thing. As I was studying mechanical engineering at the industrial secondary school, which I really enjoyed, I had no problem cutting and building a certain device or inventing a new solution to a practical task. In short, I had a completely different approach to that of my theoretically “beefy” friends from comprehensive secondary schools.

So from your story I think that going to Brno to study at Brno University of Technology must have been a natural choice...

It wasn’t that straightforward. In my senior year, I was determined to study at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University in Prague. But then came a day that changed my destiny. Although I had already been accepted to Prague, I went with my classmates to Brno to the open day of the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering BUT. The plan was that in the morning we would walk around the stands of the different fields of study and then go out for a beer. Well, I went there mainly for the beer (laughs). At one very deserted stand, where I was interested in a physics textbook on display, I was told that it was “a pretty unusual field, something between physics and engineering”. As a mechanical engineer and physics lover, this intrigued me a lot, so instead of going to the pub I went to the labs, which completely blew me away. As I was returning home on the last evening train, I was already determined to go to BUT instead of Charles University. And I have never regretted that decision.

And then how did you get into nanotechnologies specifically?

That’s actually a natural continuation of the story I’ve been telling you. I’ve been really into manual labour since I was a kid. I used to work in my grandfather’s workshop, carving wood, building go-karts... At the same time, I always wanted to take things apart, to experiment with them, to discover what was inside, to search for the essence. I also had a passion for astronomy, which attracted me from a philosophical point of view. I wondered how it was possible that it all worked like that. But here, too, I was interested in the technical side of learning about the universe. These tendencies naturally resulted in my becoming more interested in experimental astrophysics than theoretical astrophysics: when I read today about how state-of-the-art space telescopes work, it’s quite easy for me to understand the technical stuff. It’s more like I sometimes have to learn why a particular instrument is used to study, for example, the atmosphere of a planet. Well, thanks to BUT, I found out that there was a field of study that was still called physical engineering at that time. As the name suggests, it combines both worlds: there is both engineering and physics, and the focus is on experimental work in laboratories.

So if I understand correctly, the field of physical engineering has become the field of nanotechnology.

Yes, during my studies, the word “nanotechnology” was added, which made the field “sexier”. Professor Šikola, a very important name at our institute, who was already the director here at that time, brought these new nanotechnologies here. Professor Liška, who founded the institute, was an optician, which is a field that is also very close to my heart, given my enthusiasm for astronomy. I then combined these two interests and am now working on the optical properties of nanostructures. So all my life I have been working with light, through which we still get most of our information about the universe, but also about the microworld. So astronomy remains my big hobby, but what I’ve ended up doing professionally is nanophotonics.

Electron microscopes are an integral part of nanotechnology laboratories, allowing us to look into the elementary structures of matter. What was it like when you first saw an atom with your own eyes?

The first time I saw an atom was, of course, in a picture that wasn’t mine. But during the fourth year of my studies, I went to Vienna on Erasmus, where I got into Professor Varga’s excellent group doing what is called scanning probe microscopy, a technique that was among the first ones to image atoms. There I saw first-hand how these things work. For five months, you had to do the daily routine of coming to the lab in the morning, preparing the sample for two hours, cooling the system... And so on and on. Only after five months of laborious shoveling did we finally get to atomic resolution, and I got to see the “magic balls” with my own eyes. It was an incredible feeling.

Could you describe it more? The famed science fiction author and visionary Arthur C. Clarke made the famous statement that very advanced technology is de facto indistinguishable from magic. So what does one experience when one is initiated into one of nature’s deepest mysteries, so to speak?

Perhaps most of all, at that moment, I felt a deep respect for those who invented the device. Everything that had to be done before one could look inside of matter in this way... For me, it was only a five-month effort, but for them, it was a much longer journey lined with incredible work. They had to literally work out every technological detail to solve an infinite number of details with absolute precision and accuracy. So it was, in fact, a lifelong journey, at the end of which stood one “visible” atom. And we’re at the subatomic resolution nowadays, which is a whole different level. So, hats off to all those who thought this up and made it happen.

There is most likely no doubt about the future and prospects of nanotechnology, but in which sector or field do you think nanotechnological developments are most important or useful for mankind?

This is quite a tricky question; nanotechnology is now penetrating so many areas of life that we could rather look for fields where it is not applicable. If we talk about general trends, then one of the big challenges that humanity has to solve is energy conservation. If we take electro-mobility, or storing and transporting renewable energy, all of this places huge demands on the quality of batteries. This is where nanotechnology is helping us a great deal. Another area is certainly artificial intelligence. This may look like a programming thing, but we have to realize that for the IT to work, it has to have very powerful electronics. Although the term electronics already sounds a bit inappropriate because it is based on the word “electron” and today’s technologies are already starting to use completely different physical principles from those based on classical transistors. There is a lot of talk about quantum computers, but nobody knows yet how such computers will work, as there are still several approaches. One of the possibilities that we are looking at is the use of light, i.e. information carried by a photon, which would have the advantage that systems using light would not need cooling to low temperatures. This is also related to communication equipment. Today, 5G is basically an obsolete technology, 6G is already being used in science, so we are actually moving into terahertz technologies.

And are there other important areas where our scientists shine?

Material research should certainly be mentioned. Thanks to the use of nanotechnology, a huge number of materials with unique properties are being discovered today. Today, the Czech Republic is leading the way in nanomagnetism, and thanks to Professor Jungwirth’s groundbreaking discovery, we may finally get the Nobel Prize in Physics. An area that may not be talked about as much is water filtration. It is not a given that we drink good tap water or that we can brew good beer from sewage water, and our scientists have made many important discoveries in this area, too.

And then, of course, there is the field of molecular biology, which integrates physical, chemical, biological and genetic aspects in its approach. If we take this area, from vaccines to methods of genetically modifying the code, these are actually products that can be considered nanotechnologies. The use of nanorobotics in the field of molecular biology at CEITEC BUT is being studied in detail by Professor Pumera, and his work is yielding very interesting results. Using molecular biology as an example, it can be well demonstrated how these advanced technologies help humanity, in this case in the treatment of various diseases. However, to say in which area nanotechnologies will find the most important application is a bit like gazing into a crystal ball because there could be a breakthrough discovery that will turn everything on its head in a single day. What is certain is that science is becoming increasingly multidisciplinary, and nanotechnology is finding applications in a whole array of areas.

You have already mentioned your work at CEITEC BUT. What is your role here, and what project are you currently working on?

As I have already mentioned, my focus is nanophotonics, or, simply put, the study of the interaction of light with matter at the nanoscale. At CEITEC, the so-called nanofabrication, which is the fabrication of nanostructures by lithography etc., is at an extremely good level. I’m on Professor Šikola’s team here, and we focus on the fabrication of interesting nanostructures. This kind of work is multidisciplinary and requires a really large team of people. You have to have computational engineers who can calculate how to decompose the structures to make them behave the way we need them to, then there is a group of colleagues who optimize the structures and try to make the ideal version, which is definitely not easy. And once we have the product, there has to be someone to examine if it works properly. My focus here is just that: characterization. So, I’m the experimenter in the team who optically characterizes the nanostructures.

For example, we use spectroscopic methods, where we basically look at what colour the light reflects or develops. We focus a lot on holographic microscopy, which shows the phase of the light. At the same time, we often look at the polarization states of photons, which is something that’s used a lot in quantum technologies. In terms of specific activities, we are looking at, for example, the technological use of silicon carbide or vanadium oxide, which are substances with very interesting optical properties. There are many projects, and sometimes we say that we are a group with too many projects. We are simply good at getting grants, which is, of course, the better option than not having them, but the necessary condition for success, as I mentioned, is a large and well-structured team.

Of course, the practical impact of your research is important. Can you share an achievement that is already helping people and making their lives easier?

Well, those may be strong words, we will not make bread cheaper (laughs). But we are certainly in close contact with the companies that follow our research. To illustrate that this kind of cooperation can work well, I can give you an example of the production of optical metasurfaces. These are essentially the next step on the road to removing conventional optical components and turning them into thin film. If you think of your mobile phone, you need to fit lenses in front of the photo chip, which are terribly thick, and that makes your mobile phone thick. And that’s impractical, we want to make electronics smaller. That’s what these carefully designed nanostructures can do, replacing the conventional lens. Of course, optics companies follow these trends and their customers are in turn chip manufacturers and so on. So, here, in the area of optical metasurfaces, it is a close collaboration with industry that yields practical results.

Your story must make the layman feel that nanotechnology can do wonders. So it occurs to me that aside from the Sun, the nearest star to the Earth is Proxima Centauri, which is a red dwarf. So tell me, when will a man-made nanorobot disassemble and reassemble Proxima Centauri?

Of course, now you’re referring to the cult series Red Dwarf, where nanorobots disassemble and reassemble living organisms and entire stars (laughs). Well, I’m not saying that it won’t happen because looking at – say – the genetic engineering method CRISPR has fascinating results. On the other hand, I don’t think that we’ll get to the point one day when we’ll be able to somehow transfer consciousness. In the future, though, we could certainly be able to create some kind of genetic copy with the help of nanorobots; that is not so extremely difficult; it is more about the ethical dimension. But to decompose stars, we are moving into the macroworld, it will be very difficult here (laughs). It is rather interesting to see if we can get closer to other stars, other worlds, with the help of these technologies. Today’s research suggests that in the field of space travel and interstellar flight, metasurfaces may play a very important role one day.

For me, it is the connection between the microcosm and the macrocosm that is fascinating. In your popularising lectures, you search for the limits of the universe, yet at the same time, you penetrate into the most elementary structures of matter on a daily basis. These are magnitudes and distances that are completely unimaginable to us, we cannot intuitively grasp them at all because they do not correspond to our ordinary experience. How can you reconcile these in one lecture, even in one thought or a sentence?

I will go back to my beginnings in the astronomy club. That’s probably where I first realized that if I wanted to understand how the universe, the macrocosm, works, I also had to study how the smallest world works. Even the biggest stars are made up of atoms, and if we want to know how they were formed and why they shine, we have to understand the processes at the elementary level. Well, simply put, that’s how I got into microphysics. The interesting thing is that when you get down to that elementary level, you understand that nature actually works on simple laws. Complexities like the human brain are governed by a few basic physical principles. We are on the first page of the mystery of knowledge. Physics ends somewhere with the periodic table of elements. Then a chemist comes along and creates an organic molecule. A biologist follows, starting with an organic molecule and ending with a human being. I know I can never understand how the human brain works, or even one of its cells. But then again, I’m lucky enough to go bottoms-up and understand how atoms work. It never ceases to amaze me that what works in our lab works throughout the universe. It follows the same laws and creates a complex world that fills me with beauty and wonder.

So you perceive the world in a complex way, but at the same time you can distinguish between the micro and the macro world. But there’s some “crazy stuff” going on at the quantum level for which we have no words. Compared to these “miracles”, the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales are just dry, naturalistic prose. You interact with this world every day. Aren’t you ever afraid when you come home from work, sitting in your living room, and your wife is making coffee in the kitchen, that she will walk through both kitchen doors with the cup, interfere with herself, and bring the coffee to you in the form of a wave?

Yes, that’s an accurate description of quantum superposition, that’s just the way it is in the microworld (laughs). That’s the problem with our human imagination. We keep trying to imagine with these elementary particles that it’s a ball or a wave, but it’s neither. It’s just an object of the microworld, and even the word “object” is quite misleading because it already evokes something in us. As you said, it’s just something for which we don’t have words, for which we don’t have the right concepts. Yes, the quantum world is full of weirdness, but I’ve learned to accept it, I don’t worry about it anymore. When I talk about quantum physics with my students, they often ask how this and that is possible, how this and that can work. I tell them, “Don’t worry about it! Go home, look at the beautiful stars shining, and enjoy life!”

We don’t need to understand everything in detail: we all know how to use a microwave, but few know how it works inside. A doctor using state-of-the-art equipment does not need to understand the Schrödinger equation, and yet he saves lives. Yes, there is human curiosity that wants to figure it out anyway, and that drives science forward. But we don’t need to understand the meaning of life in perfect detail to do ordinary things and be good people. And in the end, as they say, the only thing that gives life real meaning is love.

At the beginning, you have vividly described how an adept chef made it to the scientific limelight. Many years have passed since then. It’s 2025 now, and maybe there is another little boy reading this who is deciding whether his future lies in cooking or physics. What advice would you give him? Why should he follow the same path as you and choose physics?

You’ll get to experience the wow effect. I mean, the kind of effect that happens the moment you understand something. In other fields of work, even in soft sciences, it doesn’t happen that often, but in physics or engineering, you just happen to understand something in an experiment, and you get that wow effect. It’s an extremely pleasant, satisfying feeling that also drives you on because you want to experience it again.

Of course, from a pragmatic point of view, our work also offers an interesting financial perspective. But above all, it’s a fun job. I go to work happy every day, and I come home happy, too. The people I am surrounded by are very nice and kind. They have humility and respect for the world and the laws of nature. Unlike some politicians, they don’t think that they are special, they understand everything and that they can’t be wrong. As I mentioned before, “I don’t know” is definitely not forbidden to say here. One is amazed when one meets the most prominent personalities and listens to their life stories, how extremely humble they are. This shapes and reinforces the right values in you. That it’s not about having millions in the bank but enjoying your work, meeting inspiring people, and learning the best from them.

Author: Tomáš Lotocki

Source: CEITEC BUT

Bismuth as a cheaper alternative to gold

Awarded student Jiří Kabát uses an electron microscope to measure the temperature of nanoparticles

Women from BUT who move the world of science and technology

BUT has its JUNIOR STAR. Young scientist begins to build her own team

Ceramics that glow. Young scientist wins award for research into new materials for lasers and X-rays